The Post-Modern Ear

In Gurrelieder, Verklärte Nacht, and Pelléas et Mélisande Schoenberg showed total mastery of tonality and of late romantic harmony, and these great works entered the repertoire. But by the time of the Piano Pieces op. 11 Schoenberg was writing music which to many people no longer made sense, with melodic lines that began and ended nowhere, and harmonies that seemed to bear no relation to the principal voice. At the same time it was clear that Schoenberg’s atonal pieces were meticulously composed, according to schemes that involved the intricate relation of phrases and thematic ideas, and this was another reason for taking them seriously.

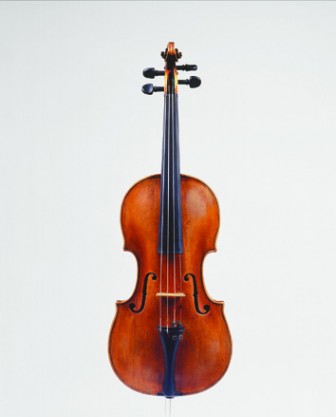

In due course meticulousness took over, leading to an obsession with structure and the quasi-mathematical idiom of twelve-tone serialism, in which the linear relations of tonal music were replaced by arcane permutations. The result, in Schoenberg’s hands, was always intriguing, and often (as in the unfinished opera Moses und Aron, and A Survivor from Warsaw) genuinely moving. Schoenberg’s pupils Alban Berg and Anton Webern developed the idiom, the one in a romantic and quasi-tonal direction, the other towards a refined pointillist style that is uniquely evocative. For a while it looked as though a genuine school of twelve-tone serialism would emerge, and displace the old tonal grammar from its central place in the concert hall. Figures like Ernst Krenek in Austria, Luigi Dallapiccola in Italy and Milton Babbitt and Roger Sessions in America were actively advocating twelve-tone composition, and also practising it. But somehow it never took off. A few works – Berg’s Violin Concerto, Dallapiccola’s opera Il Prigionero, Krenek’s moving setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah – have entered the repertoire. But twelve-tone works remain, for the most part, more items of curiosity than objects of love, and audiences have begun to turn their backs on them.

It should be remembered that those experiments were begun at a time when Mahler was composing tonal symphonies, with great arched melodies in the high romantic tradition, and using modernist harmonies only as rhetorical gestures within a strongly diatonic frame. In England Vaughan Williams and Holst were working in a similar way, treating dissonances as by-ways within an all-inclusive tonal logic, while in America inputs from film music and jazz were beginning to inspire eclectic masterpieces like Roy Harris’s Third Symphony and Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. A concert-goer in the early 1930s would therefore have been faced with two completely different repertoires – one (Vaughan Williams, Holst, Sibelius, Walton, Strauss, Busoni, Gershwin) remaining within the bounds of the tonal language, the other (Schoenberg and his school) consciously departing from the old language, and often striking a deliberately defiant posture that made it hard to build their works into a concert program. Somewhere in between those two repertoires hovered the great eclectic geniuses, Stravinsky, Bartók and Prokoviev.

The contest between tonality and atonality continued throughout the 20th century. The first was popular, the second, on the whole, popular only with the elites. But it was the elites who controlled things, and who directed the state subsidies to the music that they preferred – or at least, that they pretended to prefer. From the time (1959) when the modernist critic Sir William Glock took over the musical direction of BBC’s Third Programme, only the second kind of contemporary music was broadcast over the airwaves in Britain. Composers like Vaughan Williams were marginalised, and experimental voices given an airing in proportion to their cacophony. During the 1950s there also grew up in Darmstadt a wholly new pedagogy of music, under the aegis of Karlheinz Stockhausen. Composition, as taught by Stockhausen, consisted in random outbursts that could be described, without too much strain, as groans wrapped in mathematics. The result makes little or no sense to the ear, but often fascinates the eye with its nests of black spiders, as in the scores for Stockhausen’s Gruppen or the 6th String Quartet by Brian Ferneyhough.

The trick was successful. Stockhausen’s works received and still receive extensive, usually state-subsidised performances all across the world. His older Austrian contemporary, Gottfried von Einem, who was at the time writing powerful operas in a tonal idiom influenced by Stravinsky and Prokoviev, was in comparison ignored, not because his music is trivial, but because he was perceived to be out of touch with the new musical culture and exhibiting dangerous vestiges of the romantic worldview.

Those days are past. It is now permissible to like Sibelius and Vaughan Williams, and to believe that they are superior – which they clearly are – to Stockhausen and Boulez. It is permissible to reject the notion that tonality was made irrelevant by the atonal school, and to recognise that some of the greatest works in the tonal tradition were composed in the middle of the 20th century: Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, for example, Strauss’s Four Last Songs, Britten’s Peter Grimes, major symphonies by Shostakovitch and Vaughan Williams, Aaron Copland’s Clarinet Concerto and Appalachian Spring. Some of these – the Rachmaninoff and the Strauss – could be seen as extracting unexploited remainders from the tonal tradition. Others – Britten and Copland – were more actively engaged in renewing the tonal tradition, drawing out new kinds of melodic line and novel harmonic sequences.

In The Philosophy of Modern Music (1958) Theodor Adorno argued that tonality was nothing but the exhausted remainder of a dead tradition. But by the time he wrote it was atonality and not tonality that was exhausted. The radical modernist idiom was kept going by Darmstadt, by the system of official patronage and by the fact that real musical education, which used to be a household requirement, had been effectively destroyed by the invention of broadcasting and recording, so that few people felt confident in questioning the radical avant-garde. But the real experiments – those that drew freely on the tonal tradition and on the eclectic spirit of Western civilisation, like the Turangalila Symphony of Messiaen, the remarkable Star-Child oratorio by George Crumb, and the triple concerto of Michael Tippett – entered the repertoire without any need for the critical hype and institutional support enjoyed by Stockhausen and Boulez.

There is another reason for the brief ascendancy in those days of the avant-garde, and one that bears heavily on the future of Western music. During the course of the 20th century a wholly new kind of popular music emerged. Nobody can say, in retrospect, that the waltzes and polkas of Strauss or the operettas of Léhar and Offenbach belong to another language and another culture than the symphonies of Brahms or the music dramas of Wagner. Strauss (father and son), Léhar, Offenbach are now counted in the “classical” repertoire, just as much as Wagner, Brahms and the other Strauss. And the distinction between popular entertainment and high art is internal to their repertoire: the Overture to Die Fledermaus and the Hungarian Dances of Brahms surely stand side by side. They reach back across a century and a half to the dance suites of Bach and the ballets of Rameau – serious celebrations of joyful and light-hearted ways of being.

Only in the 20th century did popular and serious music finally divide, and the principal reason for this was jazz. The origin of this remarkable idiom is veiled in obscurity, though it is evident that it absorbed, along the way, both the syncopated rhythms of African drum music, the blues notes that come from attempting to unite the pentatonic and the diatonic scales, and the chord grammar of the Negro spirituals. The jazz idiom showed a remarkable ability to develop, so that an entirely new harmonic language grew from it, and soon became the foundation of a new kind of popular song and dance. It was this quintessentially American idiom that most got up the nose of Adorno during his time as an exile in Hollywood, and which served as his proof that tonality was destined to degenerate into short-breathed melodies and repetitious sequences.

It is true that improvisation around a “jazz standard” is a very different thing from the far-ranging musical thinking that we find in the concert-hall. A work that returns constantly to the same source for refreshment, and goes on “forever” precisely because it goes on only for a moment is a very different thing from the symphony that develops thematic material into a continuous musical narrative. But Ravel, Gershwin and Stravinsky showed how to incorporate jazz rhythm and melody and even jazz harmonic sequences into symphonic works that had some of the long-distance complexity of the classical tradition. Meanwhile there emerged a new form of popular music, on the edge of jazz, but reaching into the world of folk melody and light opera. This was the idiom of the Broadway Musical and the American Song Book. Brilliant musicians like Cole Porter, Hoagy Carmichael, and Richard Rodgers became household names, with songs that our parents knew by heart, and which defined a new kind of taste. This was music to be sung around the house, which normalised the emotions of ordinary people as they endeavoured to cope with the new world of machines, gadgets, social mobility, fast romance, and easy divorce. Thus began the great fracture in the world of music between “pop” and “classical”, in which it became ever more important for the critics to side with the classical tradition, and to find something that distinguished modern composers in that tradition from the “easy listening” and “light music” that filled the suburban bathroom.

For a while, therefore, there was an added motive for composers to take the path of radical modernism, and so to give proof that they belonged to the great tradition of serious musical thinking. A composer like Boulez, ensconced in the madhouse of IRCAM in Paris, could be, as Hamlet put it, “bounded in a nutshell and count himself king of infinite space”. Insulated from the vulgar world of musical enjoyment, sending out musical spells into the electronic ether, the composer began to live in a world of his own. That it should be Boulez who received the accolades and not Maurice Duruflé or Henri Dutilleux is explained by the enormous publicity value of difficulty, when difficulty is subsidised by the state. The radical modernists had succeeded in persuading the official bodies that they were keeping alive the flame of high art in the face of an increasingly degenerate pop culture. And for a while, following the transformation of rhythm and blues into a universal idiom of song and dance by Chuck Berry, The Beatles, and The Rolling Stones, it seemed as though they were right. What did this new popular music have to do even with the comparatively refined language and domestic charm of the Broadway musical, still less with the symphonic and operatic traditions?

But then the whole thing collapsed. Impassable divides have an ability to survive in the old hierarchical culture of Europe; but they don’t last for long in America. Composers like Steve Reich and Philip Glass had no desire to separate from their hippy friends, or to lose the most important benefit that makes the life of a composer worthwhile, namely money, and the audience that provides it. There emerged the new idiom of minimalism, in which the harmonic complexities of the modernists and those of the great jazz musicians like Monk, Tatum, and Peterson were both rejected in favour of simple tonal triads, often repeated ad nauseam on mesmeric instruments like marimbas. The result, to my ear utterly empty and the best argument for Boulez that I have yet encountered, succeeded in entering the repertoire and gaining a young and enthusiastic audience. This music is written for the concert hall, but uses the devices of pop: mechanical rhythm, unceasing repetition, fragmented and constantly repeated melodic lines, and a small repertoire of chords constantly returning to the starting point. It has joined the world of “easy listening”.

Whether Reich and Glass entitle us to talk of a new and “postmodern” idiom in the world of serious music I doubt. For this is not serious music, but a kind of musical void. Listening to Glass’s opera Ekhnaton, for instance, you will be tempted to agree with Adorno, that the musical idiom (let’s not speak of the drama) is utterly exhausted. But then along came John Adams, whose mastery of orchestration and knowledge of real tonal harmony began to redeem the minimalist idiom, and to bring it properly into the concert hall. And other American composers followed suit – Torke, Del Tredici, Corigliano, Daugherty – writing “tonal music with attitude”, inserting advanced harmonic episodes into structures that make thematic and rhythmical sense. In Britain a new wave of tonal composers has also emerged, some of them – like James Macmillan, Oliver Knussen, and David Matthews beginning as radical modernists – but all moving along the path mapped out by the great Benjamin Britten, out of the modernist desert into an oasis where the birds still sing. Such composers learned the lesson taught (however clumsily) by Reich and Glass, which is that music is nothing without an audience, and that the audience must be discovered among young people whose ears have been shaped by the ostinato rhythms and undemanding chord grammar of pop. To offer serious music to such an audience you must also attract their attention. And this cannot be done without rhythms that connect to their own bodily perceptions. Serious composers must work on the rhythms of everyday life. Bach addressed listeners whose ears had been shaped by allemandes, gigues and sarabandes – dance rhythms that open the way to melodic and harmonic invention. The modern composer has no such luck. The 4/4 ostinato is everywhere around us, and its effect on the soul, body and ear of post-modern people is both enormous and unpredictable. Modern composers have no choice but to acknowledge this, if they are to address young audiences and capture their attention. And the great question is how it can be done without lapsing into banality, as Adorno told us it must.